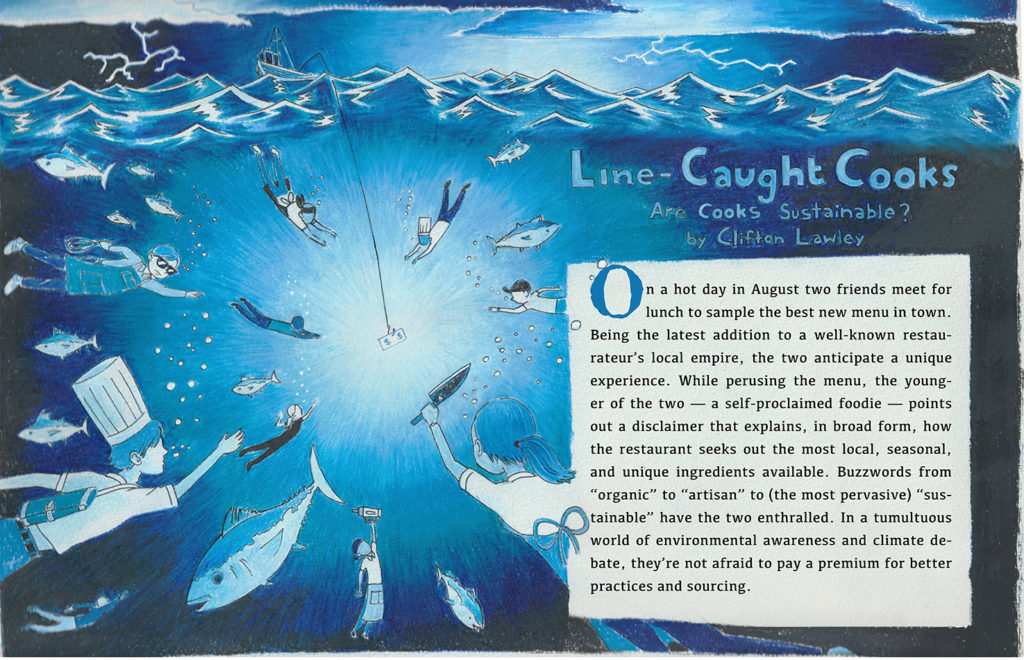

On a hot day in August two friends meet for lunch to sample the best new menu in town. Being the latest addition to a well-known restaurateur’s local empire, the two anticipate a unique experience. While perusing the menu, the younger of the two — a self-proclaimed foodie — points out a disclaimer that explains, in broad form, how the restaurant seeks out the most local, seasonal, and unique ingredients available. Buzzwords from “organic” to “artisan” to (the most pervasive) “sustainable” have the two enthralled. In a tumultuous world of environmental awareness and climate debate, they’re not afraid to pay a premium for better practices and sourcing.

After confirming the tuna is line-caught, an order is placed for the Melt-of-the-Day with a side of beet chips and gazpacho as well as a medium rare grass-fed burger and some hand-cut fries. The kitchen receives the ticket, but the dupes are on the floor. Prep and service have amalgamated into one and the young chef is struggling to maintain composure amongst the turbulent flow of service.

Staffing has been tough, so they’re running with a skeleton crew on most days. The cooks had assured the chef that they were able to take the extra hours, but their fatigue is apparent. They lucked out getting a decent stagier the day prior, but she hasn’t agreed to the job offer. Now the hot-apps cook is hung over for the third time this week. He thought he’d be fired after his last incident, but the kitchen can’t afford to lose anyone right now. The other members of the line are left to make up for his shit performance, but it’s not without the occasional slight or passive aggressive comment. Stains of beef fat and smears of chocolate adorn their aprons, telling the stories of past services. Attitudes are slightly on edge. Regardless of what they may have agreed to, they mutter their frustrations amongst themselves and push through in hopes of a short pre-dinner lull — one that never seems to come. “Add on one burger: Med-rare and a Tuna Melt,” the chef exclaims as he shuffles around the pass to drop another order of fries for the weeded line.

Later on, the chef steps out as the last entrees leave the kitchen. He left the produce and dry goods orders in the hands of his fully-capable sous chef and is heading out to meet some industry friends for beers. While drinking amongst peers, he refers to his staff as “kind of green,” lamenting how they have not been operating cohesively. He casually brags about his sous while secretly wondering if she might be after his job. His ego forms a cool confidence in public, but he’s deeply insecure. He brushes off playful jabs about how he only graduated from culinary school a few years back. “You remember when you pronounced the ‘t’ in duck confit?” says a previous coworker. “Or when you strained the veal stock right down the damn drain?” says another. There is a burst of laughter. His phone vibrates and he glances at an email. Apparently, the new bakery assistant’s social security number isn’t legit, so the owner needs the employee terminated first thing tomorrow.

Meanwhile, back in the kitchen, stations are broken down, and the floor is streaked in a soapy film. The beaten down hot apps cook drops some chicken wings in the fryer. After a liberal coating of hot sauce, he places a bowl up in the pass with an apology for his lack-luster performance. The group corrals around the bowl. They nosh at the hot flesh despondently. The ominous sounds of some EDM blaring from the dish pit sounds like white noise. After 2 minutes of silence, the bowl is mostly sauce. The porter grabs the last wing and puts the bowl in the machine. He squeegees the floor dry, while the sous chef discusses the next day’s prep with the others. It was a twelve-hour day for almost everyone, and they are doing it again tomorrow.

![]()

The diners have voiced their concern for the well-being of the fish; they prefer to know the cow died happy and that their tuna was line-caught. They’re ready to pay a substantial price for that reassurance. Yet, what about the cooks? Does the well-being of the dishwasher ever cross their mind? Do they know about our hiring epidemic or of the importance immigrants play in America’s food industry? Is the general public even remotely aware that the most over-fished resource in any restaurant right now are the cooks?

This day and age, we are inspired more than ever as chefs. Social media influences and rapid communication allow for new opportunities and fresh ideas at the touch of a finger. A chef’s pedigree and signature dishes are no longer enough to entice a line of stagiers to the door. Reputations of deeply embedded culture have taken their place on the pedestal. This is an industry well beyond saturation. There simply aren’t enough cooks to go around. Relying on conventional brigade systems and worn out hierarchies will end up shortening your access to this sparsely available supply.

Locating the kitchen-ready candidates that are legally able to work in a community is only the beginning. The prospect of them showing up for a first or second shift has become a growing concern with numerous job alternatives on every corner. A firm handshake and friendly smile at the end of an interview may end in a no show.

Immediately following the procurement of a new cook begins a long period of uncertainty in the relationship. The latest generation of cooks’ and chefs’ rudder of desires swings rapidly. Many “lifers” from the baby-boomer generation are packing their knives and finding new jobs. Not to mention, the intricate network of immigrants once relied upon by this industry has been eroded by recent shifts in government policy. Without that keystone of our foundation, the structure can hardly stick together.

Many chefs will scoff and speak bitterly of the latest generation’s fluidity, complaining that it’s harder to keep them around for long periods of employment. On the other hand, great chefs will listen to the newcomers and attempt to find lessons in their juvenile perspectives. They will sustain their staff with ease while the bitter chefs experience high turn-over. That chef’s negativity only acts as a springboard for the kitchen’s cultural decomposition. With diligent work from strong leaders, a staff can still be retained for extensive periods.

In our highly stimulated society, cooks are becoming complacent quicker than we can change the menu. Kitchen members, young and old, have their eyes on the sous chef’s position whether they’ve been cooking for two years or ten. They loathe the salads and the slicing of charcuterie on garde manger, while they gawk at the exalted flare of the grill and the ballet of sauté. Whether it’s entitlement or eagerness seems to vary from cook to cook. But, the infamous hard-assed chefs and tight French brigades that previously stifled or channeled those qualities are endangered — practically extinct. Gone are the days of screaming chefs and militant mindsets. Chefs’ and restaurant owners’ urgencies have shifted to acclimating and overcoming new challenges, calling for a new breed of talent.

The many roles of a chef continue to ebb and flow with the societal constructs surrounding them. A chef’s balance of control and adaptability can be tested on many scales. A commonly described, “strong attention to detail” points out how chefs often stay privy to the unseen nuances of the world around them. They seek out subtlety and circumvent the standardized. Most will notice the gradual sweetening of a strawberry as its season progresses. Some know which are “perfectly unripe,” therefore destined for pickling. I’ve even known chefs to accurately claim an onion to be rotten at its core before ever cutting into it. Such a level of vigilance seems to be unwavering when discussing ingredients. That same level of vigilance must be shifted to the health and mental state of the staff.

The job of a chef has been equated to the job of a conductor or even a psychologist at times. This level of adaptability lives unanimously amongst good leaders, but appears infrequently in our current “too many chefs” system. The industry recklessly continues to appease our insatiable appetite for new restaurants — from both the corporate and private sector — yet, where has this wave of chefs come from? The answer is simple. Barely capable cooks, entirely devoid of leadership skills, are being jettisoned into embroidered chef whites. It happens simply because the job needs to be filled.

At this point we need to propagate healthier kitchen cultures in existing restaurants while simultaneously pushing for less new establishments. Just because there is enough funding to build a restaurant does not mean the human resources exist to make it work. Fishing for cooks with a careless trailing net affixed to the ass-end of your new restaurant venture may get some results, but the overall outcome is bleak. Amongst the turbulence and mesh there is damage and loss. As an opposing option, instilling highly beneficial kitchen virtues combined with a genuine concern for one another is highly attractive bait for the line. The individuals acquired through this practice will be truly sustainable — the line-caught cooks America needs.

It would behoove us to work on creating that mental petition. If the public can sign on to sustaining the lives of fish, I think we can talk them into being concerned for the humans serving that fish as well. A shift in awareness can start us in the right direction. Upon establishing a public desire for healthier kitchen lives, restaurants will have to find ways to divert more focus and funding to the line cooks.

Our divided dining economy continues to favor corporate chains, putting the majority of jobs available at the behest of industry giants and franchise owners. Until the private sector of restaurants can guarantee applicants a higher quality of life, we will continue to come up short on resumes. Cooks may bounce around some local restaurants for a handful of years, but, eventually, they opt for a higher paying corporate position with full 401k and health insurance or to work for your seafood purveyor as a rep.

There are no simple fixes to an issue this complex, but general adaptability seems like a sensible place to start. Cooks need to define their hopes and goals more clearly. Business owners need to listen. Restaurant ambitions need to change variably to reflect the fluctuating capabilities of the staff.

If we have to charge more for our craft, so be it. If the front of house has to tip out the kitchen to better balance the scales, let us talk about it. We can explain to our communities what your prices reflect and where their money will go. Chefs are prominent enough public figures to be informers on why this is a push in the right direction. If we cannot do these things successfully, then we have no business in the industry at this time. Perhaps fewer cultural issues arise from the establishments that are “chef-owned,” but even still, any cook with decent credit and some capital can facilitate these titles and achievements for his or her self. As soon as he or she does so, for better or worse, they’re typically just another net in these over-fished depths. Innumerable establishments, big, small, good and awful are trolling the same open waters. Maybe this season, we bring up the nets, grab some rods, and land some line-caught cooks instead.

Contributors: Clifton Lawley & Paulie Alfredo Huerta